Twelve Bucks, Twenty Years

The strange story of a student film with a surprising shelf life.

A couple of years ago, I got a very unexpected email:

I wanted to inquire as to whether you were student at Kutztown University under the tutelage of Dr. Tom Schultz, and if you made an animated film in 1998 under the tile “Twelve Bucks”.

Apart from the misspelled name of my professor (it’s actually Schantz), this was correct. But why on earth would someone be contacting me about an old, obscure student film?

The animation class

In the spring semester of 1998, I took the sole animation class offered at Kutztown University. We studied standout animated films encompassing a variety of genres and techniques, analyzed movement and timing, and developed skills by making several of our own (very) short films with drawings, cutouts, clay, and other objects.

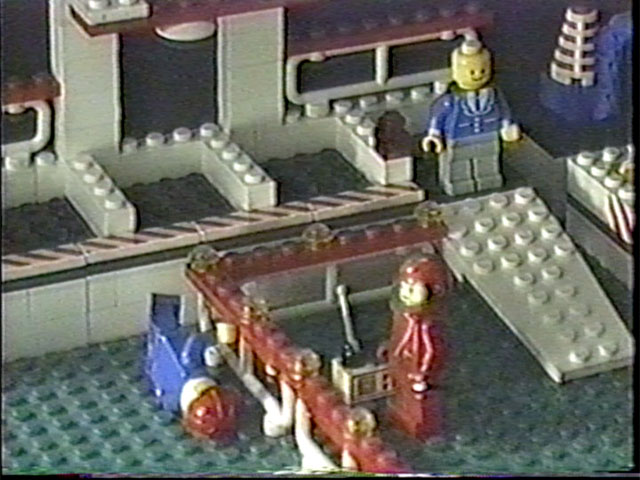

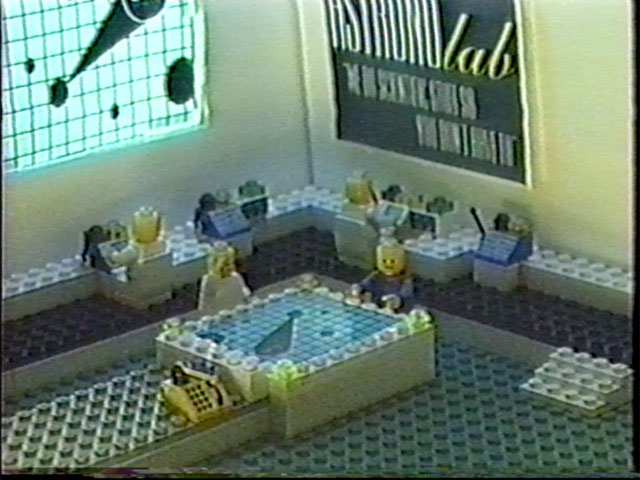

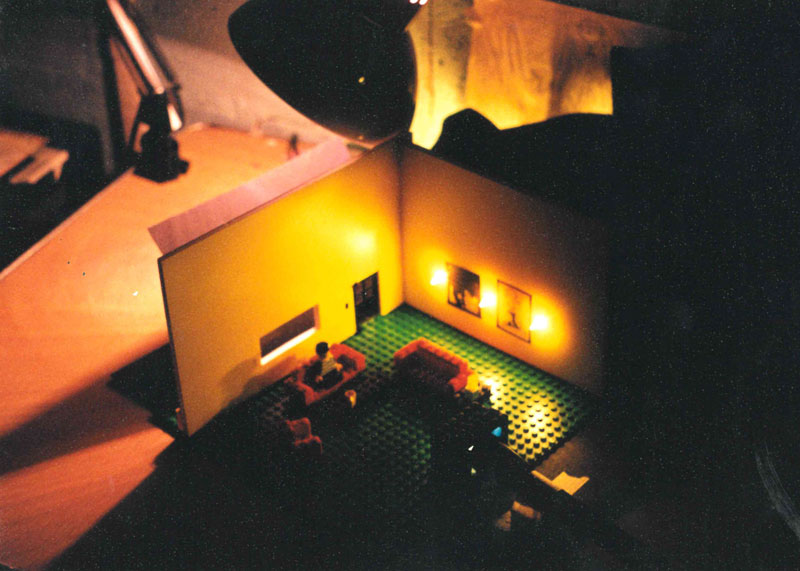

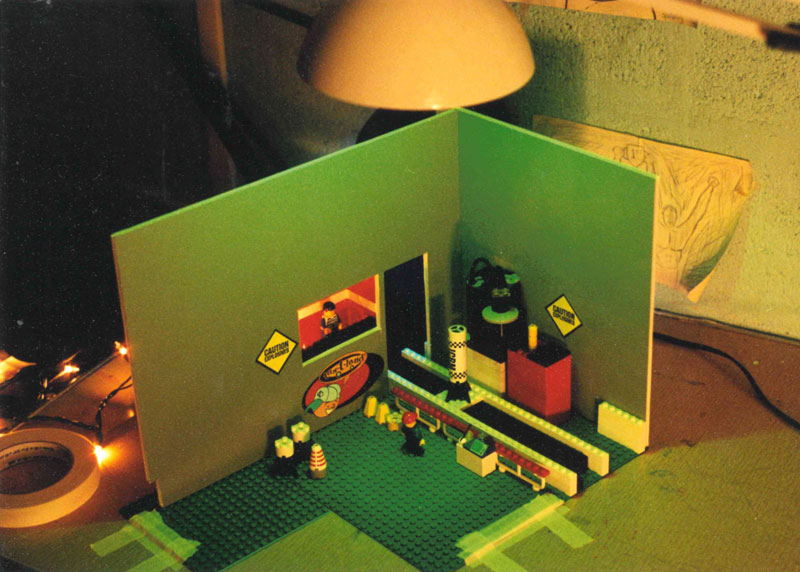

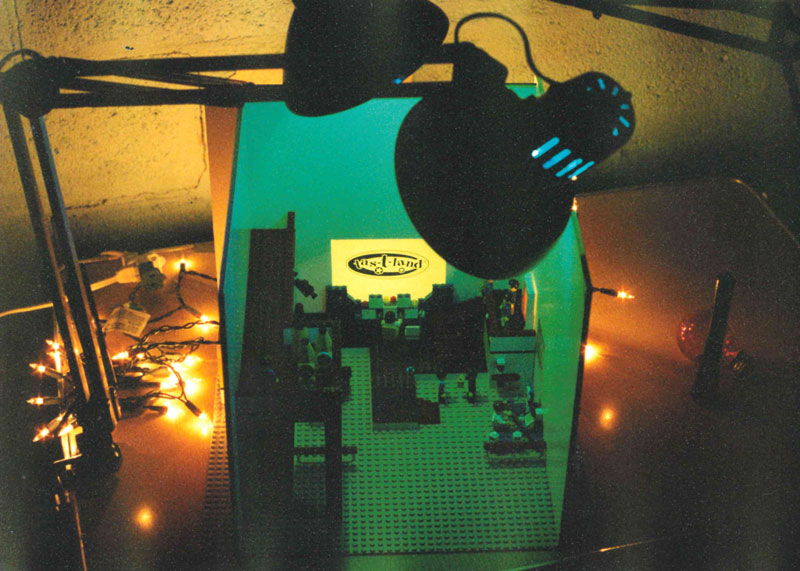

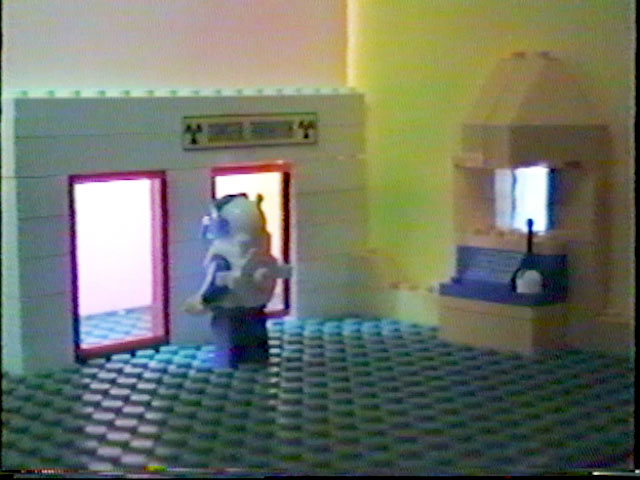

I had always wanted to be an animator, but filmmaking was a lot less accessible when I was growing up than it is now. This class was one of my first chances to really get hands-on with animation and I was thrilled. As it happened, the class coincided with my renewed enthusiasm for Lego, which I incorporated into two stop-motion films. None of our projects were required to be longer than 20 seconds (240 frames at 12 frames per second), but I was on a mission: those two Lego films, Siege on the Corporate Identity Plant and Heat, Part 2, were, respectively, 60 seconds and 120 seconds. And I didn’t want to stop there.

Siege on the Corporate Identity Plant

Heat, Part 2

Since that was the only animation class on offer, Dr. Schantz routinely oversaw independent studies for students who wanted to continue. Despite the shiny A+ I earned in that animation class, my cumulative GPA was too low to qualify for an independent study. But Schantz, the most generous and committed educator I’ve ever known, just had me sign up for an unrelated class he was teaching. In lieu of attending, I would do my independent study in animation.

The independent study

I got the idea for my next Lego film, Twelve Bucks, over the summer. Living near a college campus meant being inundated with flyers advertising unspecified work paying $12 an hour, which was a pretty good payday for an unskilled undergrad (sadly, it probably still is). I never called any of the numbers on those mysterious flyers, but I enjoyed imagining they were all thinly-veiled criminal enterprises. So a story began to emerge about a slow-witted slacker who takes a job at a seemingly innocuous corporation without realizing it’s actually a black market arms dealer. (I don’t think the premise was intentionally cribbed from the Simpsons episode “You Only Move Twice,” but there is certainly a similarity.)

I discovered the band Tuatara on a CMJ compilation that summer, and I knew right away that “Smuggler’s Cove” would be the soundtrack to my film. The song was cinematic, smooth, nocturnal, dangerous. It inspired the film’s noir vibe, languid pace, and dreamlike visual aesthetic.

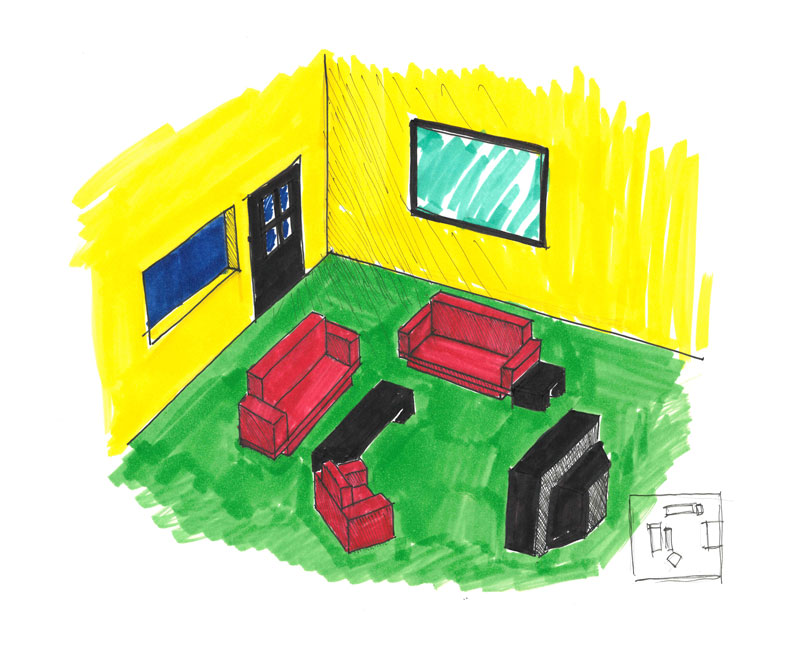

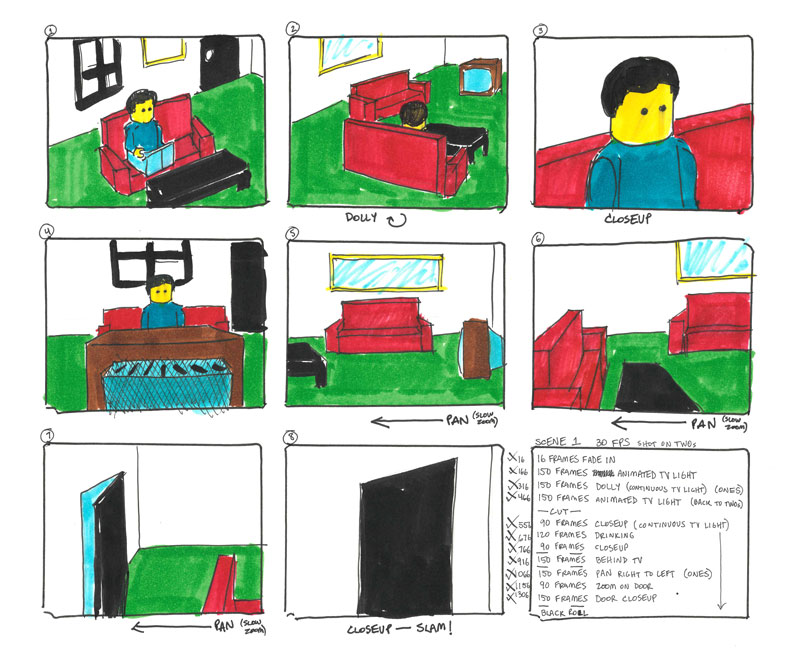

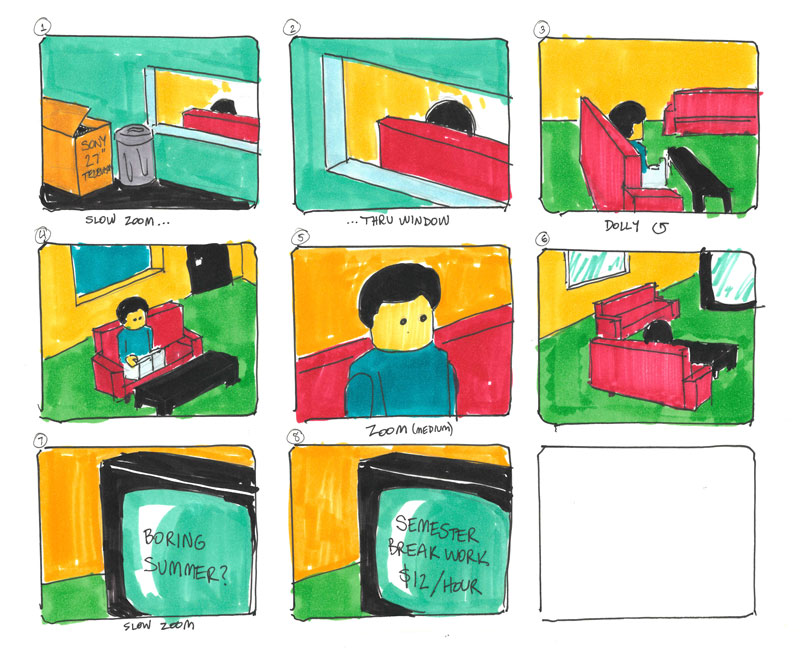

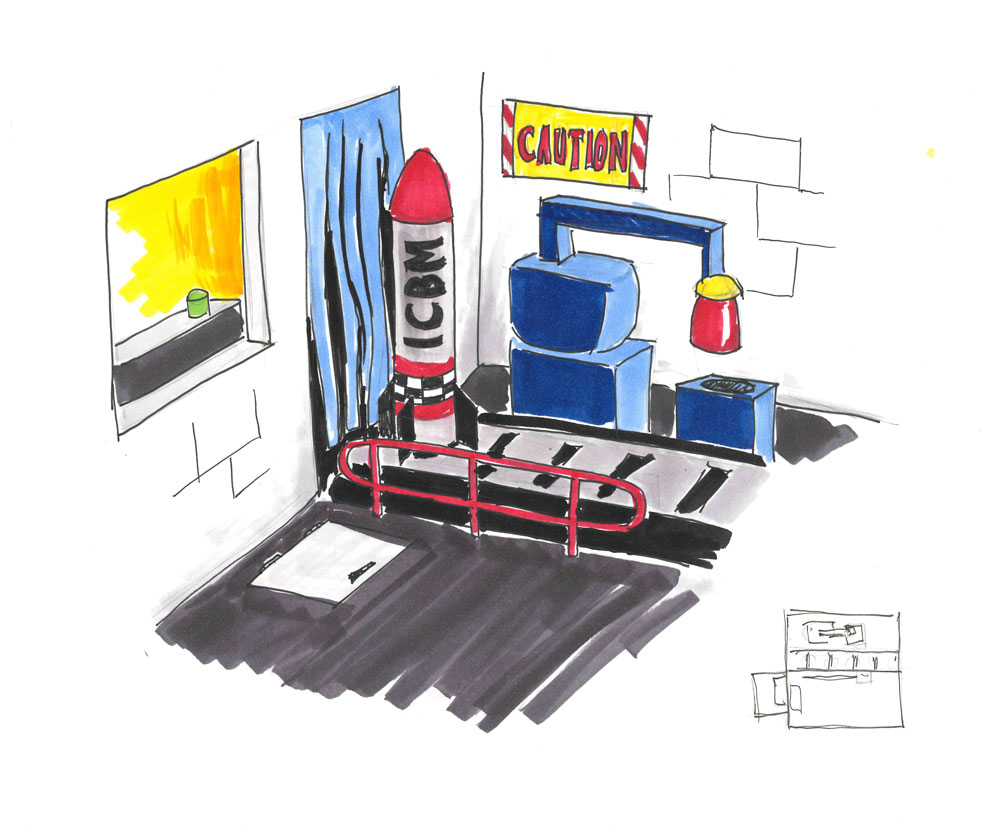

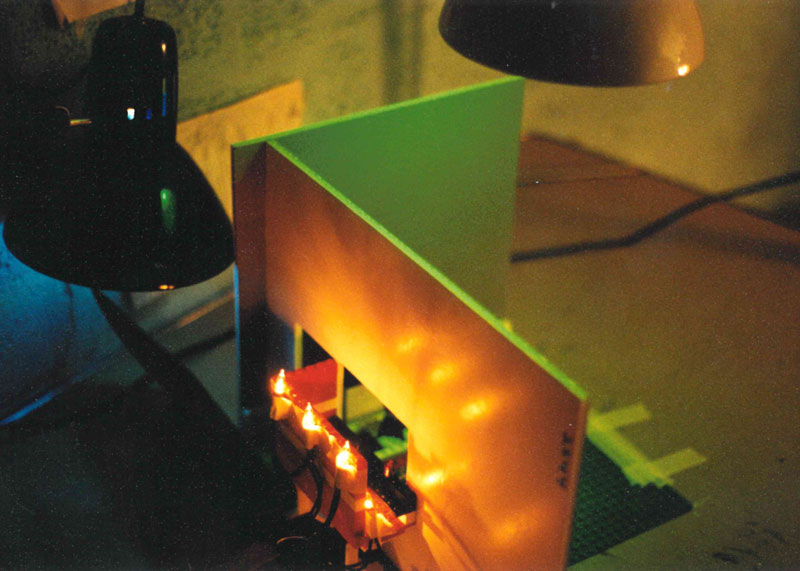

As the story came into focus, so did storyboards and set designs, and as with the previous films, shooting was an all-analog affair. Even the title sequences had to be printed on paper and animated in-camera. The university had a couple of camera rigs that shot frame-by-frame directly onto VHS. The system was intended for lo-fi pencil tests, so the quality wasn’t great, but a high quality system would probably have been wasted on someone like myself who had no idea what he was doing. I lit the film with strings of mini Christmas lights and desk lamps outfitted with colored party bulbs.

Due to various external constraints, each of my previous films had to be shot in a single session, with limited time allowed between frames taken. This led to at least one occasion where hours of work had to be redone when I made a mistake. With seven sets and a five-and-a-half-minute running time (about 4,000 frames), Twelve Bucks was impossible to shoot in that fashion. Thankfully, this time I had the luxury of spreading the shoot out over several weeks, and a telecommunications major was available to help me edit together the final footage.

Twelve Bucks was completed in December 1998. I was proud of it! It wasn’t perfect, but more than anything I had done up to that point, it felt like a thoughtful, cohesive work with an assured vision. I showed it around campus here and there, submitted it unsuccessfully to the Ottawa International Animation Festival, and finally graduated with a BFA in Communication Design the following December.

The film festival

In the spring of 2000, I caught wind of the Lost Film Fest, which united a DIY punk ethos with an underground film movement newly democratized by digital video. I gave a tape of my animations to the festival’s founder, Scott Beibin, who latched onto the politics of the Lego films. Siege on the Corporate Identity Plant lampoons the conformity of corporate culture; Heat, Part 2 is exasperated by our hostility to the environment; Twelve Bucks equates privileged complacency with complicity in violence; and all three films satirize our media diet. I don’t pretend any of them are especially profound, but I had things to say, and I was excited to find an audience, even if I was preaching to the choir.

Packaged as “The Lego Trilogy,” the three films screened in Philadelphia that August at Lost Film Fest 3.0, which doubled as a home base for demonstrators protesting the concurrent Republican National Convention. Sharing a bill with punk legend Jello Biafra was a dream I had never dared dream, but it happened that night, and the films were well received by a theater full of fired-up activists.

The internet

The Lego Trilogy became a Lost Film Fest staple and toured the country for the next few years, but in the months following its first LFF appearance:

- College compatriots and I launched Bredstik.com to share our various creative projects, including my films.

- Lego released its first Lego Studios kit, including a digital camera and stop-motion software, which created a surge in interest in Lego animation.

- Jason Rowoldt created Brickfilms.com to collect and showcase animated Lego movies.

I don’t remember if Jason found me or it was the other way around, but adding my work to Brickfilms was a no-brainer. It was nice to see a community of hobbyist animators start to form around the site, and Jason’s media savvy got us a showcase on viral video hub iFilm and some nice attention from the New York Times:

Most works are from one to five minutes, enough time to satirize just about anything, and parodies of “Star Wars” and “2001: A Space Odyssey” are a staple of brick films. But there is a small group of auteurs, like Mr. Weychert, whose film work suggests a movement away from a fascination with novelty toward headier terrain.

Storyboards for As Good As Soma, an abandoned film project.

I watched the Brickfilms community with some interest for a little while, and I started making plans for a new film, but those plans stalled and I moved on to other things. It looked like my Lego animation career had run its course. Until…

The restoration

I wanted to inquire as to whether you were student at Kutztown University under the tutelage of Dr. Tom Schultz, and if you made an animated film in 1998 under the tile “Twelve Bucks”.

The inquiry came from someone in grad school studying moving image archiving. Because I’m bad at email, our correspondence fizzled out, but I did a little Googling to try to understand why anyone would be interested in my 18-year-old student film. To my astonishment, I found a forum discussion from 2015 that was all about Twelve Bucks:

Twelve Bucks is a very important part of brickfilms history. Released in 1998, it is one of only a handful of brickfilms known to be made before the millennium, and it is one of the first brickfilms to be darkly serious (even if it still contains touches of dark humor). This brickfilm is intelligent, and expects its audience to be intelligent too.

I think Twelve Bucks’ style and narrative is still one of the best examples around, and doesn’t even get many rivals today. It’s very impressive that Rob Weychert went in this direction with a brickfilm in 1998. It also has some great indoor lighting and screen effects. This is a very important film that everyone should see.

My mind was blown. Not only did my scrappy little film have fans, they were still actively discussing it nearly two decades after it was made!

Recently, I heard from two more random fans in the space of a month, and I hatched a plan. The only digital version of the film, which was put online in 2000, is low-res and heavily compressed. Since this year is its 20th anniversary, and at least a handful of people are apparently still interested, why not release a “restored” version?

I dug out my old VHS tapes, turned them over to Future Analog to be digitized, and recut Twelve Bucks from the original masters. Apart from some rudimentary color correction, one small editing tweak, and some ghosting introduced by the ravages of time, the restored version looks mostly like it did 20 years ago, including the original low-tech title sequences (which I had replaced with a fancier Flash-animated version when I originally put the film online).

Whether or not you’re an avid brickfilm enthusiast, I hope you enjoy it. Thanks for watching!