Not of These Earths

There is little I enjoy quite as much as spending an entire afternoon in a movie theater, so I often lament the fact that I missed out on the heyday of the double feature. Of course, in this day and age, I’m able to curate my own double (or triple, or quadruple) features in the privacy of my own home, which I do often. I might watch a string of sequels, a pair of films with a thematic link, or the collected works of one director. In this case, though, I decided to watch three different versions of the same movie, which itself was originally part of a theatrical double feature.

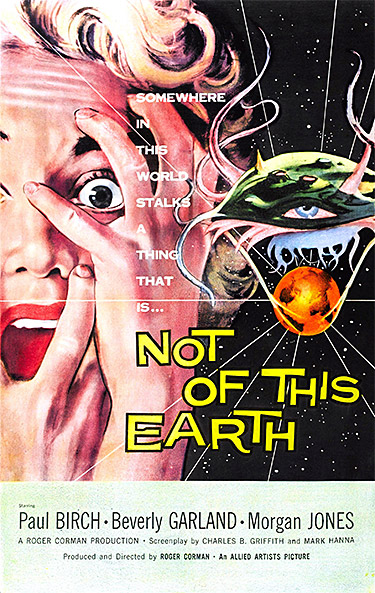

Not of This Earth (1957)

Not of This Earth is an early example of a premise conceivably determined by the proverbial writer’s room dartboard. In this case, the first two darts landed on “space” and “vampire.” There was no need to throw a third.

To its credit, this space vampire saga doesn’t merely put Bela Lugosi in a space suit. Instead, we have a seemingly eccentric old man who is actually a spy from another world. His name, naturally, is Paul Johnson. He and the people on his home planet of Davanna are all dying of a disease that causes their blood to evaporate, and he is on the hunt for a fresh supply to bring home. While on his mission, he enlists the help of Doctor F.W. Rochelle to diagnose his strange blood disease, and nurse Nadine Story to give him the regular transfusions that will keep him from drying up. When Nadine’s duties call for her to move into his house, it doesn’t take her long to suspect that Johnson’s eccentricities are masking something sinister, and as Johnson’s assistant Jeremy notes, visitors have a tendency to disappear.

When Not of This Earth was released in 1957, producer/director Roger Corman had about a dozen independent features under his belt – all of which, it should be noted, he directed in a three-year span – so the dollar-stretching acumen that would make him famous in the decades to come was already well-developed. There is never any question that this film was made on the cheap: the lights cast harsh shadows, the sets reverberate with every syllable, and the scenes all have the ring of an underdeveloped first take. And for a film with such a fantastic premise, its aesthetic is remarkably austere. The few bits of props and scenery which might generously be called special effects could easily have been quickly cobbled together from the inventory of a local hardware store. Even the film’s opening crawl sets expectations low: “If the events you are about to witness are unbelievable, it is only because your imagination is chained!”

Much of this can probably be chalked up to strategy. Since it was released as the bottom half of a double bill, Not of This Earth didn’t really need to be as thrilling as the top half did (especially when that film had a title with as much inherent promise as Attack of the Crab Monsters, also produced and directed by Corman). Corman might also have hoped to capitalize on the Cold War paranoia that described other sci-fi movies at the time – after all, the villainous Johnson is a devious foreign invader from a place ravaged by nuclear war, trying to harvest a substance that is the very definition of red.

Though Not of This Earth is not without good qualities (most notably Beverly Garland’s confident portrayal of Nadine, and the Aspergian character Paul Birch creates for Johnson, especially on the rare occasion it’s played for laughs), no one would have expected it to be much more than a footnote in the murky pantheon of 1950s B movies. So it was a bit of a surprise when Jim Wynorski remade it in 1988.

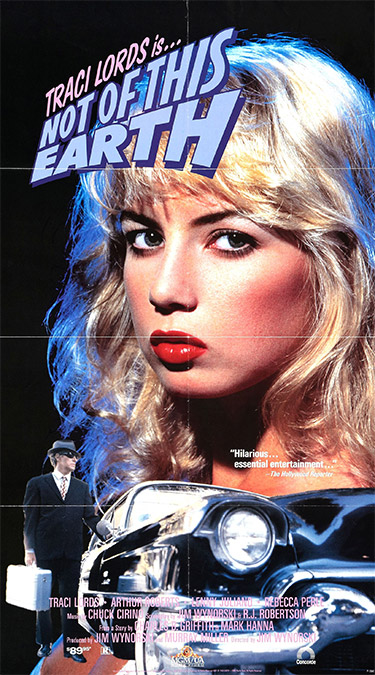

Not of This Earth (1988)

At this point in time, Roger Corman’s legacy was solid and still growing. He had a devoted following of cult film fans, had only lost money on one of his hundreds of pictures, and had helped launch the careers of megastars and auteurs like Jack Nicholson, Peter Fonda, Martin Scorsese, and Peter Bogdanovich. Having grown up watching Corman’s films, Jim Wynorski had been thrilled to begin working for him a few years earlier, and the first feature he wrote and directed under Corman’s wing, Chopping Mall, was a hit. As legend has it, Wynorski’s version of Not of This Earth was made with the same production schedule and (inflation-adjusted) budget as the original, and used a nearly identical script, but it had one important element the original had lacked: a controversial star.

Traci Lords had earned notoriety by hoodwinking the adult film industry and starring in dozens of hardcore pornographic films while she was still a minor, before the authorities caught on in 1986. Not of This Earth is her first “mainstream” movie, and her last appearance naked onscreen.

An exploitation filmmaker couldn’t ask for a better audience to exploit than the one created by the Traci Lords brouhaha. Viewing the work that made her famous was now ethically objectionable and punishable by law, so this was the public’s first chance to morally and legally see what all the fuss was about. Wynorski does as expected, depicting Lords (as Nadine, the nurse) in various states of undress, and just in case that isn’t enough, he replaces several of the bit players from the original film with other naked women.

Having slightly less experience with the constraints of low-budget filmmaking than Roger Corman did when he made the original, Jim Wynorski makes ample use of that most tried-and-true method of corner-cutting in Not of This Earth: stock footage. Two scenes are lifted wholesale from other Corman productions, and the opening title sequence is a montage of the most outrageous moments from Battle Beyond the Stars, Forbidden World, Galaxy of Terror, Humanoids from the Deep, Battle Beyond the Sun, and Piranha. Ironically, it has the opposite effect of the apologetic crawl that opens the original Not of This Earth; in this one, the greatest hits compilation that makes up the titles is probably the most enjoyable part of the movie, and it’s all downhill from there.

If Wynorski’s version is slightly more successful, it is only because it is more knowingly campy. In particular, Lenny Juliano seems to be having a ball playing Jeremy, the villain’s wise-cracking, licentious assistant. And the cheap effects employed in the service of Johnson’s deadly, alien powers are designed to be more fun than frightening. But it still suffers from many of the same overall quality issues that made the original mostly unremarkable.

Nevertheless, a third incarnation appeared in 1995.

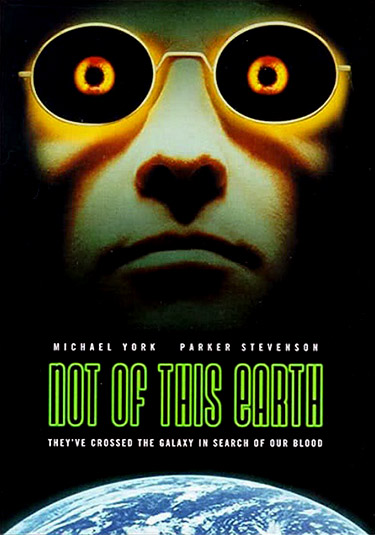

Not of This Earth (1995)

One wonders if the third version of Not of This Earth exists solely to make its predecessors look good by comparison. Where the previous films have some flashes of cleverness and are occasionally made charming by their flaws, this one fumbles nearly every opportunity. Where composer Chuck Cirino’s 1988 soundtrack conjures genuine personality from its synthesized constraints, Jeff Winkless’s 1995 MIDI score is generic and lifeless. Where Roger Corman’s most prominent 1957 special effect is a pair of milky contact lenses for his villain, the flashy CGI available to visual effects director Perry Harovas in 1995 is far less ominous. And where both Corman and Jim Wynorski could at least get their casts to make an effort, most of the actors working under director Terence Winkless are sleepwalking. Indeed, Richard Belzer – arguably the most accomplished actor in any of the films – gives one of the worst performances. Granted, he doesn’t have much to work with. None of the dialog is retained from the previous films, and the stuff that replaces it is painfully flat.

These were familiar symptoms of B movies in the ’90s. As they were pushed further out of theaters and relegated almost exclusively to the home video market, filmmakers and audiences were increasingly disconnected from each other, and the kind of giddy enthusiasm that had enabled plenty of standout genre pictures in decades past was becoming rare. The failure of Not of This Earth’s third incarnation to breathe any new life into its well-mined concept makes it a sadly typical product of its time.

Spanning nearly forty years, these three generations of Not of This Earth are an interesting case study in the evolution of B movies (and cinema in general), and how they respond to the expectations of the marketplace and social mores as they change over time. Foremost, the sex and violence in Wynorski’s 1988 version simply wasn’t possible for Corman’s 1957 version. And yet, as Wynorski’s film gets closer to its thirtieth anniversary, it seems unlikely that a 2018 version of Not of This Earth could shock a 1988 audience. Time will tell, unless this particular tale of vampires from space is permanently retired, and if Winkless’s limp 1995 attempt is any indication, that might not be so bad. Not of This Earth probably deserves a rest.